Sensory acuity refers to how accurately a stimulus can be located. The degree of acuity varies between areas of the body depending on function, for example, the fingertips require a greater sensory acuity than the forearm.

This is determined by 3 things:

- Lateral inhibition of the central nervous system (CNS)

- Two-point discrimination

- Synaptic convergence and divergence

Lateral Inhibition

Lateral inhibition is the ability of excited neurones to inhibit the activity of neighbouring neurones. This prevents the lateral spread of neuronal activity. Consequently, this creates an increased contrast in excitation between neighbouring neurones, allowing better sensory acuity.

Lateral inhibition is a key component in visual processing as it helps to increase the contrast and enhance the perception of edges. Lateral inhibition is also important when processing fine touch, as the amplified differences in neuronal activity allow a person to better pinpoint the area being touched.

Two-point Discrimination

Two-point discrimination is the ability to discern between two points touching the skin. Hence, it describes the minimum distance required between two simultaneous stimulations applied to be registered. This distance tends to vary depending on which part of the body we are testing. For example, in the fingertips, the minimum distance required to achieve this phenomenon is smaller than the distance required further up the arm.

Two factors determine two-point discrimination: density of sensory receptors, and size of neuronal receptive fields. The higher the number of sensory receptors in a region, the more accurate the sensory perception of the region. Fingertips have 3-4 times more density of sensory receptors than the hand.

Each neurone has a specific sensory space that if simulated will result in the activation of that particular neurone. This space is known as the receptive field of that neurone. The receptive field varies in size. The larger the receptive field is, the greater the area that it detects changes in but also less precise perception, and vice versa. Hence, areas with the most sensitive two-point discrimination will have a high density of receptors with small receptive fields. Where receptive fields overlap, this results in reduced precision of perception.

Synaptic Convergence and Divergence

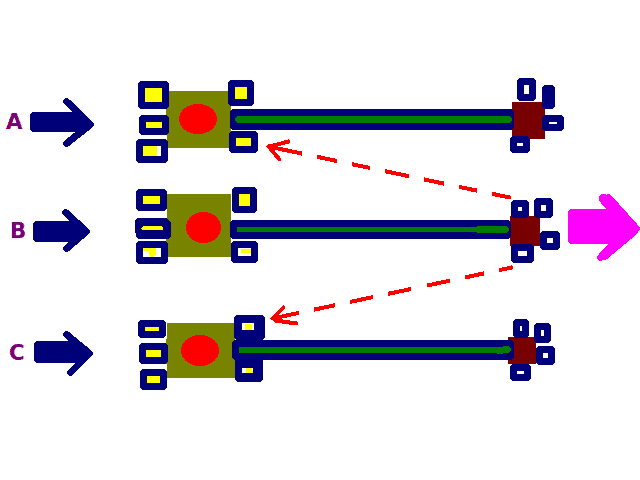

Synaptic convergence is when several first-order neurones converge on one second-order neurone. It results in reduced acuity as a signal from multiple receptors converges on one neurone. However, this process also increases the overall sensitivity to stimulation as the activation of multiple receptors can activate the second-order neurone.

Synaptic divergence involves one first-order neurone stimulating several second-order neurones. It allows for a more precise sense of perception by amplifying the signal from a single receptor or area.

Clinical Relevance – Testing Two-Point Discrimination

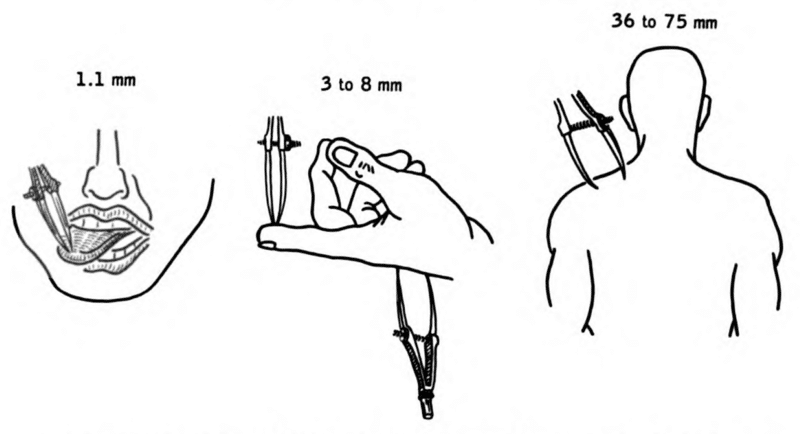

Two-point discrimination is often tested within a neurological examination to assess tactile perception. It should be carried out with the patient’s eyes closed to prevent the interference of visual stimuli.

A calliper, or reshaped paperclip, should be used and the patient should be asked when touched to report whether they felt one or two points. The smallest distance between two points that still results in the perception of two stimuli is recorded as the two-point threshold.

The two-point threshold can be reduced by either damage to a peripheral nerve or damage to the Dorsal Column-Medial Lemniscal pathway.