Labour (also known as parturition) is the physiological process by which a foetus is expelled from the uterus to the outside world. There are three separate stages, characterised by specific physiological changes in the uterus which eventually result in expulsion of the foetus. At this point, the foetus becomes known as a neonate.

This article shall consider the different stages of labour, and we will discuss the physiology unpinning each of them. We will then consider some clinically relevant points.

Initiation of Labour

The exact process by which labour is initiated in humans is not fully understood. Throughout the third trimester, involuntary contractions of the uterine smooth muscle begin to occur – these are known as Braxton Hicks contractions. They occur irregularly and are thought to be a form of “practice contraction”, but they are not regarded as a part of labour.

For labour to commence, cervical ripening needs to occur. Furthermore, the uterine myometrium needs to become more excitable. A woman is typically said to be in labour when regular, painful contractions lead to effacement and dilatation of the cervix.

Cervical Ripening

Cervical ripening refers to the softening of the cervix that occurs before labour. Without these changes, the cervix cannot dilate.

It occurs in response to oestrogen, relaxin and prostaglandins breaking down cervical connective tissue; prostaglandins are of particular importance. Prostaglandins are produced by the placenta, the uterine decidua, the myometrium, and the membranes. Their synthesis increases throughout the third trimester as a result of an increase in the oestrogen:progesterone ratio.

Ripening involves:

- A reduction in collagen.

- An increase in glycosaminoglycans.

- An increase in hyaluronic acid.

- Reduced aggregation of collagen fibres.

This means that the cervix offers less resistance to the presenting part of the foetus during labour.

Myometrial Excitability

The relative decrease in progesterone in relation to oestrogen that occurs towards the end of pregnancy helps to facilitate an increase in the excitability of the uterine musculature. This is because progesterone typically inhibits contractions and oestrogen increases the number of gap junctions between smooth muscle cells, increasing contractility.

Mechanical stretching of the uterus also helps to increase contractility – this means as the foetus grows, the contractility of the muscle increases.

The Role of Oxytocin

Oxytocin is responsible for initiating uterine contractions. Throughout pregnancy it has limited action as there are a low number of oxytocin receptors and it is inhibited by relaxin and progesterone.

At around 36 weeks gestation, under the influence of oestrogen there is an increase in the number of oxytocin receptors present within the myometrium. This means the uterus begins to respond to the pulsatile release of oxytocin from the posterior pituitary gland.

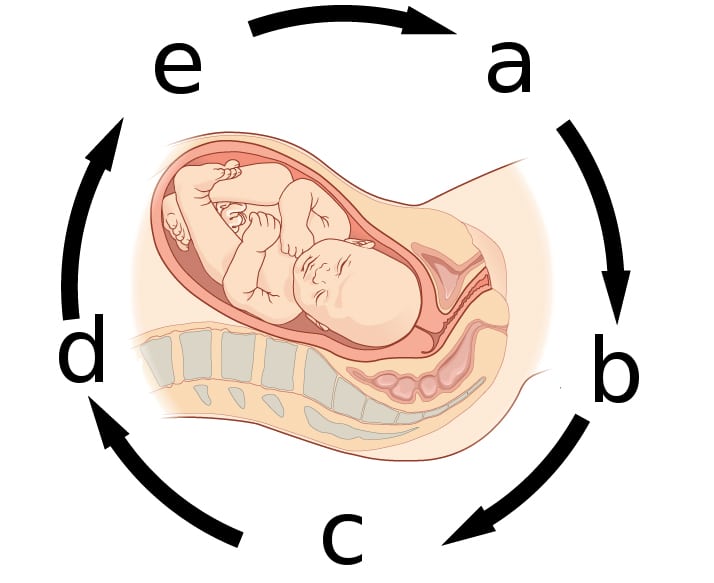

Oxytocin production is increased by afferent impulses from the cervix and vagina. This means that contractions result in a positive feedback loop to the posterior pituitary gland to release more oxytocin, leading to stronger contractions which then drives the process of labour. This is known as the Ferguson reflex.

Fig 1 – Diagram to show the positive feedback loop of oxytocin during labour. (a) Brain stimulates pituitary gland to secrete oxytocin. (b) Oxytocin carried in bloodstream to uterus. (c) Oxytocin stimulates uterine contractions and pushes baby towards cervix. (d) Head of baby pushes against cervix. (e) Nerve impulses from cervix transmitted to brain.

The Stages of Labour

First Stage

The first stage of labour results in the creation of the birth canal and lasts from the beginning of labour until the cervix is fully dilated (~10cm). The maximum size of the birth canal is determined by the pelvis – the pelvic inlet is typically around 11cm, but this may increase slightly during pregnancy as ligaments soften under the influence of hormones.

Throughout the first stage contractions will occur every 2-3 minutes. If foetal membranes have not already ruptured, they do during this stage. It consists of two phases:

- The latent phase – slow cervical dilatation over several hours which lasts until the cervix has reached 4cm dilatation.

- The active phase – faster rate of cervical dilatation until 10cm dilatation reached, the typical rate is around 1cm/hr in nulliparous women and 2cm/hr in multiparous women. This phase should not normally last longer than 16 hours.

Once the cervix is dilated the foetal head is able to descend, remaining flexed to maintain the smallest diameter possible.

Second Stage

This lasts from full dilatation of the cervix until the foetus has been expelled. Uterine contractions become expulsive and this pushes the foetus through the birth canal. There are two stages of this:

- The passive stage – this lasts until the head of the foetus reaches the pelvic floor, at which point the woman experiences the desire to push. Rotation and flexion of the head are also completed in this stage. It typically only lasts a few minutes.

- The active stage – the pressure of the foetal head on the pelvic floor results in an urge to “bear down”. During this stage the woman pushes in conjunction with her contractions in order to expel the foetus.

The fibres of the myometrium are specially adapted to drive the process of labour as they do not fully relax following each contraction. This steadily reduces the uterine capacity, so the pressure inside becomes stronger as labour progresses and helps with expulsion of the foetus. Contractions are made more forceful and frequent by the actions of two hormones:

- Prostaglandins – more intracellular calcium is released per action potential, increasing the force of contractions

- Oxytocin – lowers the threshold for action potentials, increasing the frequency of contractions

The active stage typically results in delivery of the foetus after 40 minutes in nulliparous women and 20 minutes in multiparous women. If it takes longer than one hour, spontaneous delivery becomes increasingly unlikely.

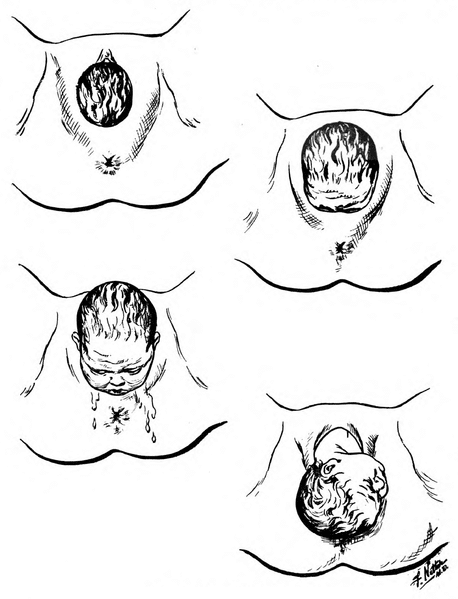

Delivery

Once the head of the foetus reaches the perineum, it extends in order to come up and out of the pelvis. Following delivery of the head, it rotates by 90 degrees to assist with delivery of the shoulders.

The anterior shoulder delivers first, coming under the symphysis pubis while the body flexes laterally and posteriorly to aid passage. Following this the body flexes laterally and anteriorly to help deliver the posterior shoulder.

Once the shoulders have been delivered the rest of the body follows.

Third Stage

The third stage of labour follows delivery and lasts until the placenta has been delivered. Uterine muscle fibres contract to compress the blood vessels supplying the placenta, which then shears away from the uterine wall. Contractions continue until the placenta and membranes have been delivered.

This stage typically lasts around 15 minutes and up to 500ml blood loss is normal. Normally bleeding is controlled during this stage by multiple mechanisms:

- Contraction of the uterus constricts blood vessels in the myometrium

- Pressure is exerted on the placental site once it has been delivered by the walls of the contracted uterus

- The normal blood clotting mechanism

Clinical Relevance – Induction of Labour

This is the process of initiating labour artificially. It is generally performed when the risk of remaining in utero outweighs the risks of initiating labour – this is typically between 40 and 42 weeks gestation in a normal pregnancy.

There are three main methods for inducing labour:

- Vaginal prostaglandins

- Amniotomy

- Membrane sweep

The method chosen depends on any risk factors present in the woman, the gestational age and the Bishop score (which assesses cervical ripeness).

Complications include failure of induction, uterine hyperstimulation and an increased rate of further interventions compared to spontaneous labour.

Further information on the induction of labour can be found here.