The hypothalamus is a small organ which lies deep within the centre of the brain. It plays an important role in various physiological functions, including the regulation of pituitary hormones, body temperature regulation, and appetite control.

In this article, we will consider the hypothalamus’ structure, function, and clinical relevance.

Structure of the Hypothalamus

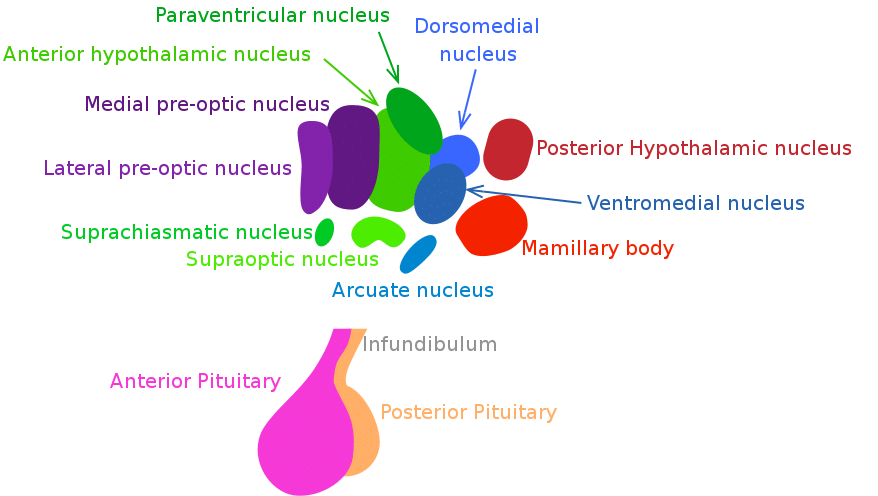

The hypothalamus is made up of three units.

Anterior (Supraoptic) Nuclei

These comprise the preoptic, medial, and lateral areas. There are numerous distinct nuclei within this area, the details of which are beyond the scope of this article. Together, they are involved in a variety of functions including thermoregulation and hormone regulation.

Middle (Tuberal) Nuclei

This area is responsible for the control of appetite, the release of growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH), and the regulation of sleep via orexin neurons in the lateral hypothalamus.

Posterior (Mammillary) Nuclei

Nuclei in this area help regulate body temperature by causing shivering and blocking sweat production and also play a key role in memory formation.

Hypothalamic-Adenohypophyseal Axis

The hypothalamus is highly interconnected with other parts of the central nervous system and has a close relationship with the pituitary gland. This is known as the hypothalamic-adenohypophyseal axis (hypophysis = pituitary, adenohypophysis = anterior pituitary).

Two categories of hormones are produced in the hypothalamus:

- Hypophysiotropic hormones (affecting the pituitary gland)

- Tropic hormones (targeting other endocrine glands)

Both types are released from the median eminence (a part of the hypothalamus that extends outwards) into the hypophyseal portal system. This carries them to the anterior pituitary. Depending on the hormone, the pituitary will either begin secreting or stop secreting hormones into the circulation.

Clinical Relevance – Cranial Diabetes Insipidus

Cranial diabetes insipidus describes a scenario whereby the hypothalamic production of ADH is inadequate. ADH normally acts on the kidneys to help retain fluid. A relative lack of ADH results in the kidneys excreting excess free water. Patients present with polyuria (increased urination) and polydipsia (increased thirst). Unlike people with diabetes mellitus, patients with this condition have stable blood sugar levels

Clinical Relevance – Prader-Willi Syndrome

Prader-Willi syndrome occurs spontaneously in most instances, and direct inheritance is comparatively rare. The hyperphagia (excess eating) that occurs in this condition is caused by abnormal hypothalamic activity, resulting in a lack of satiety.

Signs and symptoms include:

- Obesity caused by food-seeking behaviours: hoarding or foraging for food, eating inedible items, and stealing money to buy food

- Constant urge to eat

- Slower metabolism

- Decreased muscle mass