Pain is a somatic and emotional sensation that is unpleasant in nature and is associated with actual or potential tissue damage. Physiologically, the function of pain is crucial for survival and has a major evolutionary advantage. Behaviours that cause pain are often dangerous and harmful. This means they are generally not reinforced and repeated, reducing the likelihood of causing damage.

The classification of pain is complicated. There are many different types of pain, each arising through unique mechanisms. Types of pain include: sharp, prickling, thermal, or aching pain. The origin of pain can be somatic, visceral, thalamic, neuropathic, psychosomatic, referred, or illusionary. Pain can also be acute or chronic in nature.

This article will provide a general overview of a ‘classic’ picture of pain i.e. the pain we feel when we stub our toe or touch something sharp. It will focus on how the pain pathway is initiated and processed within the spinal cord.

The General Pain Pathway

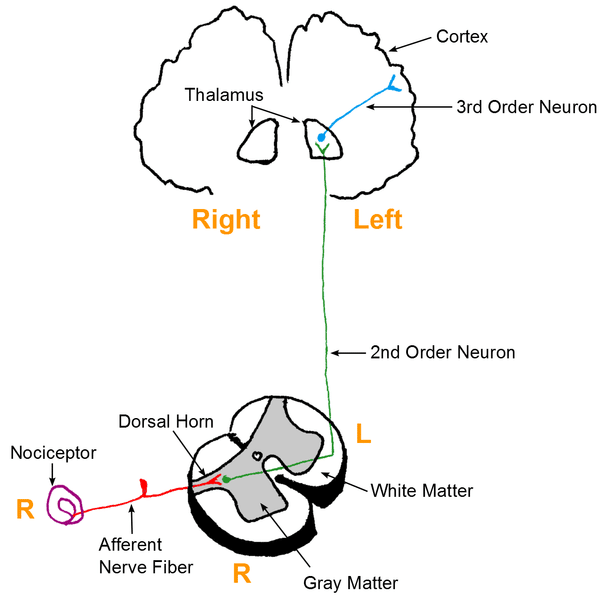

Within the pain pathway there are 3 orders of neurones that carry action potentials signalling pain:

- First-order neurones – These are pseudounipolar neurones which have cells bodies within the dorsal root ganglion. They have one axon which splits into two branches, a peripheral branch (which extends towards the peripheries) and a central branch (which extends centrally into the spinal cord/brainstem).

- Second-order neurones – The cell bodies of these neurones are found in the Rexed laminae of the spinal cord, or in the nuclei of the cranial nerves within the brain stem. These neurones then decussate in the anterior white commissure of the spinal cord and ascend cranially in the spinothalamic tract to the ventral posterolateral (VPL) nucleus of the thalamus.

- Third-order neurones – The cell bodies of third-order neurones lie within the VPL of the thalamus. They project via the posterior limb of the internal capsule to terminate in the ipsilateral postcentral gyrus (primary somatosensory cortex). The postcentral gyrus is somatotopically organised. Therefore, pain signals initiated in the hand will terminate in the area of the cortex dedicated to sensations of the hand.

The below is a simplistic generalisation for the pain pathway, however, a more detailed model is beyond the scope of this article.

Activation of First Order Neurons

Nociceptors

Some first-order neurones have specialist receptors called nociceptors which are activated through various noxious stimuli. Nociceptors exist at the free nerve endings of the primary afferent neurone.

Since nociceptors are free nerve endings this means they are unencapsulated cutaneous receptors. This is opposed to encapsulated cutaneous receptors (e.g. Merkel’s discs) which detect other sensory modalities such as vibration and stretching of the skin.

Similar to other sensory modalities, each nociceptor has its own receptive field. This means one nociceptor will transduce the signal of pain when a particular region is skin is stimulated. The size of receptive fields varies throughout the body and there is often overlap with neighbouring fields.

Areas such as the fingertips have smaller receptive fields than areas such as the forearm. In addition, they have a larger density of free nerve endings within this receptive field. This difference is important as it allows for greater acuity in detecting a sensory stimulus.

The size of cortical representation in the somatosensory cortex of a particular body part is related to the size of the receptive fields in that body part. For example, because the fingertips have small receptive fields, and thus a greater degree of sensory acuity, they have a larger cortical representation.

Nociceptors can be found in the skin, muscle, joints, bone, and organs (other than the brain) and can fire in response to a number of different stimuli. Different types of nociceptors exist:

- Mechanical nociceptors – detect the distension of skin (stretch) and pressure which elicit sharp, pricking pain.

- Chemical nociceptors – detect exogenous and endogenous chemical agents, such as prostanoids, histamines etc.

- Thermal and mechano-thermal nociceptors – detect thermal sensations that elicit slow and burning, or cold and sharp in nature, pain.

- Polymodal nociceptors – detect mechanical, thermal, and chemical stimuli.

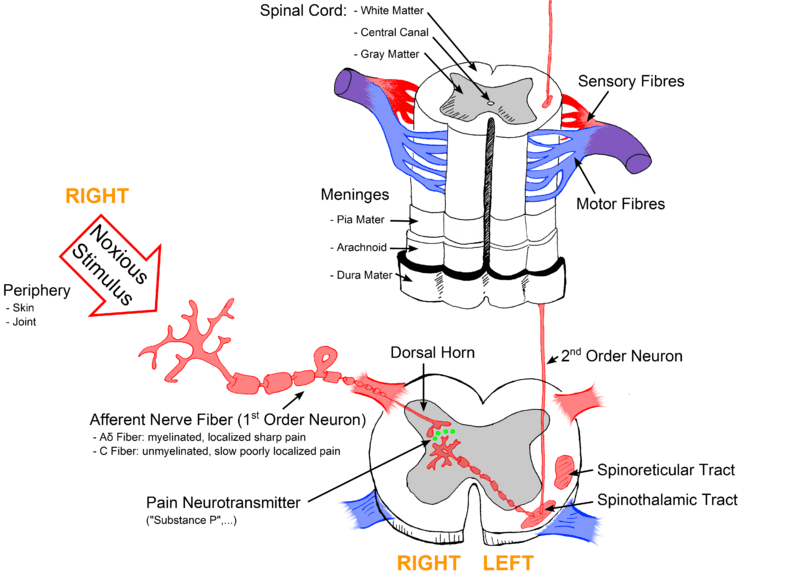

Transmission to the Spinal Cord

Signals from mechanical, chemical, thermal, and mechano-thermal nociceptors are transmitted to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord predominantly via Aδ fibres. These myelinated fibres have a low threshold for firing and a fast conduction speed. Hence, they are responsible for transmitting the first pain felt.

In addition, Aδ fibres permit the localisation of pain and form the afferent pathway for the reflexes elicited by pain. Aδ fibres predominantly terminate in Rexed laminae I where they mainly release the neurotransmitter, glutamate.

Polymodal nociceptors transmit their signals into the dorsal horn through C fibres. C fibres are unmyelinated and a slow conduction speed. For this reason, C fibres are responsible for the secondary pain we feel which is often dull, deep, and throbbing in nature. These fibres typically have large receptive fields and therefore lead to poor localisation of pain.

Compared to Aδ fibres, C fibres have a high threshold for firing. However, noxious stimuli can cause sensitisation of C fibres and reduce their threshold for firing. C fibres predominately terminate in Rexed laminae II (known as substantia gelatinosa) and release the neurotransmitter substance P. Other neurotransmitters are released by primary afferent neurons terminating within the spinal cord such as aspartate and vasoactive peptide.

A variety of factors are released upon tissue damage which leads to the activation of nociceptors. These include:

- Arachidonic acid

- Potassium

- 5-HT

- Histamine

- Bradykinin

- Lactic acid

- ATP

Many of these factors are also pro-inflammatory and lead to acute inflammation in the area of damage.

Altered Perception of Pain

Hyperalgesia

Hyperalgesia describes the phenomenon where there is an enhanced sensation of pain at normal threshold stimulation. The pathophysiology of hyperalgesia is believed to arise from the sensitisation of nerves in and around the damaged area. Sensitisation means that these nerves have a reduced threshold for firing as a result of noxious stimuli. An example of peripheral sensitisation is a release of substance P by the free nerve endings which stimulates surrounding cells to release molecules, potentiating pain.

Sensitisation can also occur centrally within the spinal cord. The pathophysiology is thought to arise from an increase in the number of NMDA receptors, as well as increased sensitivity of NMDA receptors to glutamate. These changes occur on the dendrites of second-order neurones and are a result of prolonged glutamate release from first-order neurones (due to persistent nociceptor activation).

Central sensitisation leads to hyperexcitability of second-order neurones within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.

Allodynia

Allodynia is a sensation of pain experienced in response to a stimulus that was previously not painful. It is also observed in and around areas affected by noxious stimuli.

Hyperalgesia and allodynia are features of a physiological response to pain but can also be observed in pathology. For example, neuropathic pain is characterised by hyperalgesia, allodynia, and spontaneous firing of nociceptors due to nerve damage.

Descending Modulation of Pain

Within the central nervous system, there are three types of opioid receptors which regulate the neurotransmission of pain signals. These receptors are called mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptors.

They are all G protein-coupled receptors and their activation leads to a reduction in neurotransmitter release and cell hyperpolarisation, reducing cell excitability. Exogenous opioids, such as morphine, provide excellent analgesia by acting on these receptors. Likewise, our body contains endogenous opioids which can modulate pain physiologically. There are three types of endogenous opioids:

- Β-endorphins – which predominately binds to mu opioid receptors

- Dynorphins – which predominately bind to kappa opioid receptors

- Enkephalins – which predominately bind to delta opioid receptors

Opioids can regulate pain on a number of levels, both within the spinal cord, brain stem, and cortex. Within the spinal cord, both dynorphins and enkephalins can act to reduce the transmission of pain signals in the dorsal horn. This is because the post-synaptic ends of second-order neurones have opioid receptors within the membrane. In addition, the pre-synaptic ends of first-order neurones contain opioid receptors.

When endogenous opioids act on these receptors it reduces neurotransmitter release from the first-order neurone, and causes hyperpolarisation of the second-order neurone. Together, this reduces the firing of action potentials in the second-order neurone, blocking the transmission of pain signals.

Clinical Relevance – World Health Organisation (WHO) Analgesic Ladder

The WHO has produced a step wise process for managing pain. There are 3 steps in this ladder. If the pain is not controlled by the first step, the patient will progress on to the next step.

- Step 1 (mild to moderate pain) – Non-opioid (paracetamol, aspirin or NSAID) +/- an adjuvant (low dose tricyclic antidepressant/ anticonvulsant/ muscle relaxant/ other NSAIDs)

- Step 2 (moderate to severe pain) – Weak opioid (codeine/ tramadol) +/- a non-opioid +/- an adjuvant

- Step 3 (Severe pain) – Strong opioid (morphine/ fentanyl/ diamorphine) +/- a non-opioid +/- an adjuvant