Action potentials in ventricular myocytes trigger the calcium (Ca2+) entry necessary for their contraction. Their synchronicity, characteristic shape and length all help protect these cells against abnormal electrical activity. When these protective mechanisms go wrong, it can be potentially life threatening.

In this article, we will look at how action potentials spread in ventricular cells, their shape and modulation in disease states. In order to understand ventricular action potentials, it is important to understand the basics how an action potential forms. For explanations of these concepts, please visit the pages on resting membrane potential and action potentials.

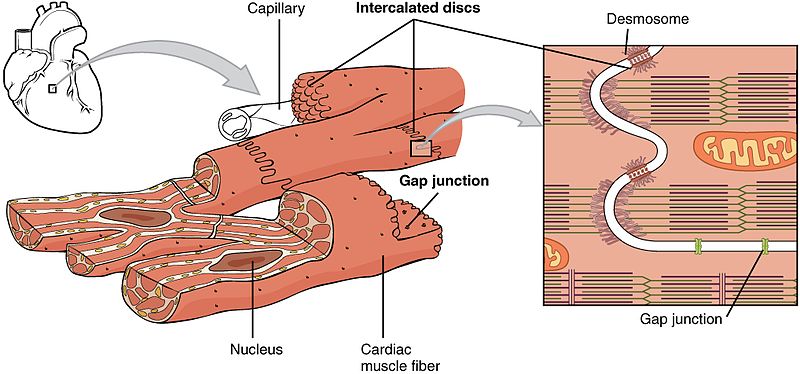

Gap Junctions

Gap junctions are regulated pores that connect adjacent cardiac myocytes. They are made from proteins called connexins, which together form a unit called a connexon. Connexons are embedded in the plasma membrane of adjacent cells, essentially connecting them to each other. Gap junctions are mostly located at the intercalated discs, which are are found at either end of the cell.

When the connexons of two adjacent cells come together, they can form a channel which allows the cytosol of both cells to mix. This allows ions to easily pass from cell to cell, meaning the cells become electrically coupled.

Electrical coupling ensures the heart’s electrical activity is synchronised. This is because when ions cause an action potential in one cell, it can spread to adjacent cells as ions will quickly diffuse through the gap junction down a large electrochemical gradient. This almost instantaneously evokes an action potential in the adjacent cell. This process is repeated across the entire ventricle, allowing the ventricle to contract synchronously. Gap junctions also ensure a unidirectional spread of the action potential, which means blood flows smoothly in one direction and ventricles are emptied properly.

Phases of Ventricular Action Potentials

Ventricular action potentials are split into 5 phases (phases 0-4 inclusive). Rather confusingly however, phase 4 is the baseline that the membrane potential begins and ends at, so is actually the first phase.

Like any action potential, each phase is driven by the opening and closing of a variety of specific ion channels. This is because opening an ion channel allows ions to flow across the membrane, pushing the membrane potential closer to the respective ion’s equilibrium potential. This creates an effective way of controlling the membrane potential in a predictable manner. The main channels responsible for each phase (sodium, potassium and calcium) and how they affect the membrane potential will be explored here.

Phase 4 – Baseline

Potassium (K+) currents are the main determinant of the resting membrane potential as the membrane is far more permeable to K+ than any other ion. At rest K+ channels are open, therefore resting membrane potential tends towards the equilibrium potential for K+ (EK), which is roughly -70mV.

Phase 0 – Fast Depolarisation

Voltage-gated Na+ channels open in response to depolarisation that spreads into the cell through gap junctions. The influx of Na+ ions further depolarises the cell, which in turn causes more Na+ channels to open. This continues in a positive feedback mechanism to cause fast and steep depolarisation.

The Na+ channels become inactivated almost immediately after opening. It is not possible for them to open while in this inactivated state. These channels can only recover from inactivation to enter the closed state at very negative membrane potentials. This means that as long as the myocyte is depolarised, these Na+ channels will not be able to open and creates a refractory period where another action potential cannot be induced.

Phase 1 – Notch

These transient opening K+ channels rapidly repolarise the cell before the plateau phase. Therefore they set the membrane potential of the plateau phase. Greater K+ currents during this notch phase allow more repolarisation so that the plateau occurs at lower voltages. Fewer K+ currents means that less repolarisation occurs and the plateau phase occurs at higher voltages.

Phase 2 – Plateau

L-type Ca2+ channels are located in the T-tubules that penetrate the cell. These channels are in close proximity to the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Therefore the Ca2+ that enters through them binds to ryanodine receptors located on the SR.

This triggers massive Ca2+ release from the SR through a channel in the ryanodine receptor. This phenomenon is called calcium-induced calcium release (CICR). The majority (75%) of Ca2+ that enters the cell comes from the SR. CICR is essential for excitation-contraction coupling within the cell. Calcium ions bind to troponin C and initiate the movement of tropomyosin away from the myosin head binding site on the actin molecule – permitting contraction.

N.B. this method of calcium release is different in skeletal muscle.

Phase 3 – Repolarisation

Fig 2 – Diagram showing phases of the ventricular action potential, with the main ion movements highlighted.

As Ca2+ channels close, K+ currents succeed in repolarising the cell, driving the membrane potential toward EK. During this phase, Na+ channels will begin to recover from inactivation as the membrane potential becomes more negative. This permits the cycle to restart.

Clinical Relevance – Hyperkalaemia

In hyperkalaemia, the raised extracellular K+ makes the environment outside the cell more positive and decreases the resting membrane potential. This increases the driving force for Na+ entry during fast depolarisation as it is repelled by the positive charges of K+. The extra K+ outside also increases the driving force for K+ entry during repolarisation. This makes repolarisation happen quicker. This may cause tachycardia in the short term.

Eventually, the cell will re-equilibrate moving closer to the new EK. As hyperkalaemia makes EK less negative, this moves the membrane potential closer to the threshold.

At these depolarised potentials voltage-gated Na+ channels become inactive. This means fewer Na+ channels are available to participate in action potential generation. Action potentials are less likely to occur under these conditions causing bradycardia in the long term.

Clinical Relevance – Hypokalaemia

In hypokalaemia, the lower extracellular K+ reduces the driving force for Na+ entry in fast depolarisation as there are fewer positive charges outside the cell (increased resting membrane potential). Less K+ outside the cell also reduces the driving force for K+ entry during repolarisation. This makes repolarisation take longer. Therefore, this causes bradycardia in the short term.

Eventually, the cells will re-equilibrate and move closer to the new EK. Hypokalaemia makes the EK more negative so this moves the membrane potential further from the threshold.

At these hyperpolarised potentials fewer voltage-gated Na+ channels are inactive. This means more Na+ channels are available to participate in action potential generation. Action potentials are more likely to occur under these conditions causing tachycardia in the long term.