The large intestine is the final section of the gastrointestinal system before the rectum. In this section of the GI tract water is reabsorbed and any remaining waste material is stored as faeces to be removed. Further information on the anatomy of the large intestine can be found here.

This article shall consider how waste material is moved through the large intestine and clinical conditions that are relevant to its function.

Haustral Shuttling

The large intestine is naturally separated into segments known as haustra. Along the course of the walls are groups of cells called pacemaker cells. These send signals to the smooth muscle cells on the walls of the large intestine causing them to contract at regular intervals.

The contraction causes the food to be churned in the intestine exposing the gut contents to a larger surface area of epithelium maximising absorption. Each group of cells control a certain number of haustra. The pacemaker cells closer to the ileum emit signals slightly faster than those towards the end of the length of bowel. This gradient allows a gentle progression of bowel contents towards the rectum.

Mass Movement

Whilst haustral shuttling occurs continuously mass movement only occurs once or twice per day. This involves a sudden, uniform peristaltic contraction of smooth muscle of the gut which originates at the transverse colon and rapidly moves formed faeces into the rectum, which is normally empty. The result of this is feeling the urge to defecate.

The contraction may be stimulated by eating. When this occurs it is called the gastro-colic reflex.

Clinical Relevance – Ulcerative Colitis

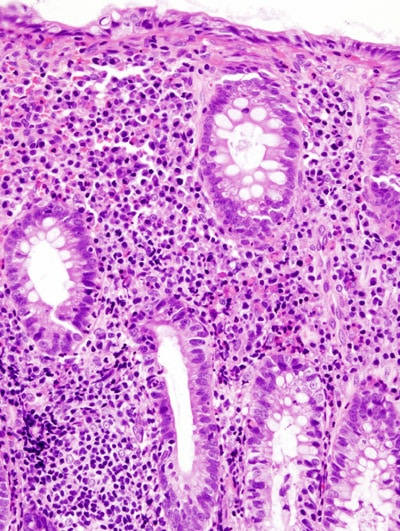

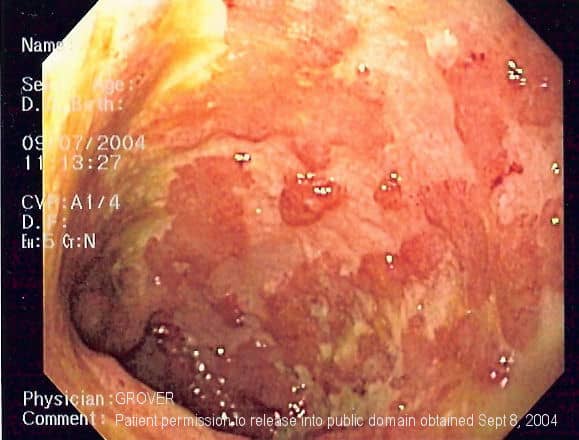

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a structural condition caused by the inflammation of the large bowel. It can affect any part of the large colon or rectum. It will usually stop at the caecum, although some patients may have irritation of the ileum due to backwash ileitis. Inflammation is continuous, although up to 30% of patients may experience patchy inflammation, making endoscopic diagnosis uncertain. UC patients usually experience bloody diarrhoea, tenesmus, pain and fatigue.

There may also be extraintestinal features of the disease present such as; uveitis, scleritis, arthritis, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum and mouth ulcers.

Fig 1 – Histology of a patient’s large intestine with active Ulcerative Colitis.

To confirm a diagnosis of UC patients will undergo a detailed history and examination. This will then be followed by blood tests which would include an FBC for anaemia, U & Es, LFTs, amylase for pancreatitis, CRP for infection and ESR for inflammation. Faecal calprotectin levels can also be assessed, as it is a sensitive marker for inflammation of the bowel and distinguishes between IBD and IBS. Endoscopy and CT scans can also be utilised to assist with diagnosis and to assess the severity of the condition.

Treatment is dependent on the severity and location of disease. Severe disease requires urgent intravenous steroids and ‘rescue’ therapy with anti-TNF-alpha agents or ciclosporin – although some patients may require emergency colectomy. Mild to moderate disease is managed step-wise with a variety of inflammatory agents such as aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, anti-TNF-alpha agents and thiopurines.

Surgery is sometimes performed acutely, however many patients undergo elective surgery due to drug side effects or failed medical treatment. There are broadly two types of surgeries, both of which require temporary ileostomy formation. It is important to make sure that a patient can take care of a stoma and the psychological implications of this need to be addressed, especially as patients may be quite young.

Fig 2 – Endoscopy of a patient with Ulcerative Colitis.

Crohn’s Disease

Like Ulcerative colitis, this condition is also an example of an IBD. This disease can affect any part of the digestive tract from the mouth to the anus.

Symptoms include diarrhoea (which may be bloody if there is severe inflammation), abdominal pain, fever, and weight loss.

Other features of Crohn’s Disease may include mouth ulcers, skin rashes such as pyoderma gangrenosum or erythema nodosum, anaemia, arthritis and eye inflammation. Perianal fistulae are also quite common compared to UC patients.

In colonoscopies, biopsies can often be taken where patients with Crohn’s Disease show a transmural pattern of inflammation. There may be granulomas that are noncaseating as well as lymphoid aggregates. A cobblestone-like appearance is also often described on colonoscopy. Skip lesions are also present.

Management

- Conservative- smoking cessation, improved hydration, high-fibre diet

- Medical treatment- antibiotics for infection, for symptomatic Crohn’s; 5-ASA, prednisolone, azathioprine, methotrexate as well as biologics