Cutaneous circulation is involved in the supplying blood to the skin. The skin is not very metabolically active and thus has relatively small energy requirements. Because of this, its blood supply is different from other tissues. Some of the circulating blood volume in the skin will flow through arteriovenous anastomoses (AVAs) instead of capillaries. AVAs play a role in temperature regulation.

In this article, we shall consider the various adaptations of cutaneous circulation.

Arteriovenous Anastomoses (AVAs)

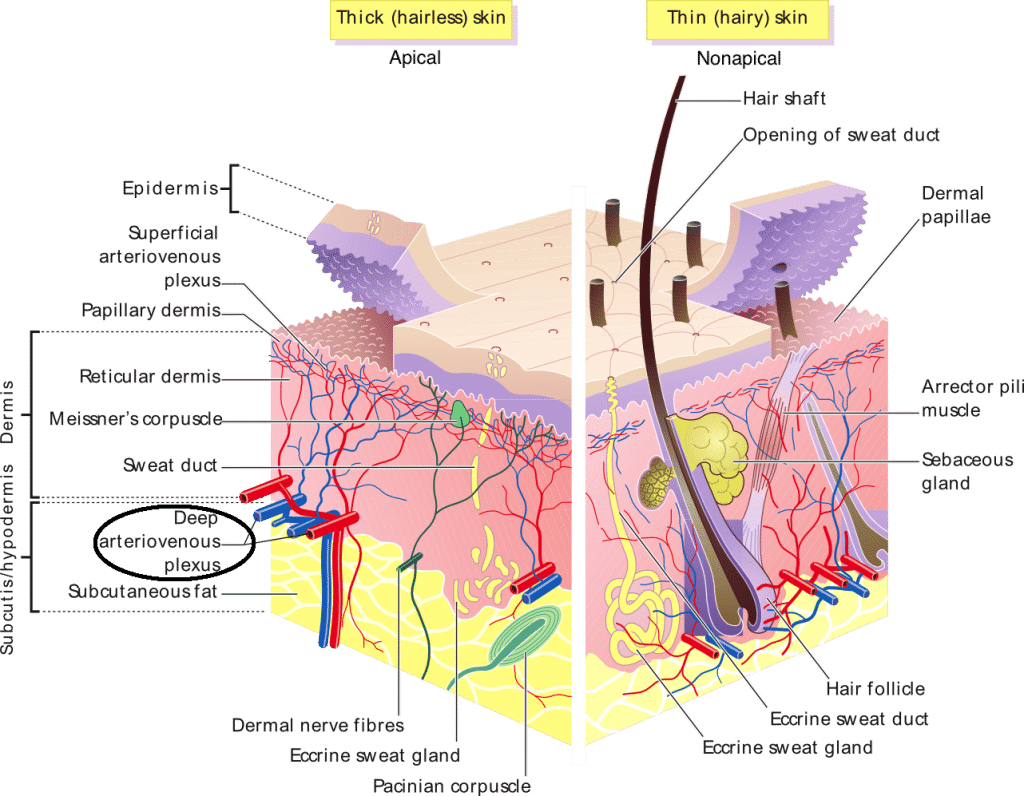

AVAs are low-resistance connections between the arterioles (smaller arteries) and venules (smaller veins). They shunt blood directly into the venous plexus of the skin, bypassing the capillaries. Since blood in the AVAs does not pass through the capillaries, they are not involved in nutrient, oxygen or metabolite transport between blood and tissues.

Apical skin is the superficial portion of skin which contains many AVAs and thus helps control the body’s core temperature.

Temperature Regulation

The skin is the body’s main heat-dissipating surface. The amount of blood flow to the skin determines the degree of heat loss and, therefore, the core body temperature. The sympathetic nervous system influences the blood flow through AVAs. At rest, the sympathetic nervous system dominates and acts to constrict the AVAs.

The thermoregulatory centre in the hypothalamus detects changes in core temperature. The thermoregulatory centre regulates the body’s temperature by altering the level of sympathetic outflow to the cutaneous vessels.

In high core temperatures:

- Sympathetic innervation is decreased, reducing the vasomotor tone in the AVAs.

- More blood flows through the AVAs and reaches the superficial venous plexus (near the skin’s surface). This increases heat loss and reduces core temperature.

In low core temperatures:

- Sympathetic innervation is increased, increasing the vasomotor tone in the AVAs.

- Less blood flows to the apical skin (of nose, lips, ears, hands and feet). This reduces heat loss and increases the core temperature.

Fig 1 – Arteriovenous anastomoses (circled) near the dermal-epidermal junction of apical skin

Clinical Relevance – Heatstroke

Heatstroke is a life-threatening illness characterised by a core body temperature above 40°C. It occurs due to the skin’s thermoregulatory system failing and can be caused by various factors such as dehydration.

Normally, the body generates heat from metabolism and the environment, and this heat must be dissipated to maintain a normal core temperature. This occurs through cutaneous vasodilatation and increased blood flow, resulting in the evaporation of sweat. If the body is dehydrated, this mechanism becomes overwhelmed, causing the body’s core temperature to rise.

Dehydration impairs the cardiovascular response to heat, resulting in an insufficient increase in cardiac output. As a result, anaphoresis (reduced sweat production) occurs, and the body’s core temperature rises. This causes symptoms including fatigue, reduced consciousness and delirium.

Management includes immediate cooling and replacing fluids and electrolytes. Untreated heatstroke can result in other systemic effects such as arrhythmias and hepatic failure.