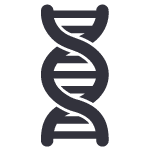

The spleen is an organ the size of a fist found in the left upper quadrant (LUQ) of the abdomen, under the protection of the inferior thoracic cage.

Information on the anatomy of the spleen can be found on our sister website.

It is multi-functional and to accommodate for this, it is a soft, vascularised organ with a fibro-elastic capsule. However, it is not one of the vital organs of the body. The spleen contains two types of tissues with different functions: white pulp and red pulp.

This article shall discuss the function of each tissue within the spleen as well as relevant clinical conditions.

White Pulp

The white pulp comprises lymph-related nodules called malpighian corpuscles which contain

- Periarteriolar lymphoid sheaths rich in T-lymphocytes and macrophages.

- A marginal zone, rich in macrophages

- Lymphoid follicles, rich in naive B-lymphocytes

Because of this, the white pulp of the spleen has a very important role in the normal immune response to infection. Antigen presenting cells may enter the white pulp, resulting in activation of the T-lymphocytes stored there. These in turn, activate the B-lymphocytes in the follicles, converting them to plasma cells which then produce of IgM antibodies initially and eventually IgG antibodies.

Pathogens may also enter the follicles directly. B-lymphocytes detect this and can then present the antigen to the T-lymphocytes. This leads to a process known as co-stimulation, in which the two cell types activate each other – so the B-lymphocyte is then able to become a plasma cell and produce antibodies against the pathogen.

The white pulp is also important in how the body deals with encapsulated bacteria e.g. Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Encapsulated bacteria tend to have a very smooth surface with a negative charge which therefore reduces the ability of phagocytes to attach and engulf the bacteria. The B-lymphocytes in the white pulp help opsonise these bacteria.

Red Pulp

The red pulp makes up roughly 80% of the spleen parenchyma. It is separated from the white pulp by the marginal zone. The red pulp is primarily made up of tissue known as the cords, which is rich in macrophages, and the venous sinus.

The functions of the red pulp include:

- Removal of old, damaged and dead red blood cells along with antigens and microorganisms – the venous sinuses have gaps in the endothelial lining which allows normal cells to pass through, abnormal cells remain in the cords and are phagocytosed by macrophages

- Phagocytosis of opsonised bacteria by macrophages

- Sequestration of platelets.

- Storage of red blood cells in case of hypovolaemia, these can then be released following an injury resulting in blood loss

- Prenatally, it is haematopoietic until about the fifth month of gestation when bone marrow becomes the main site for haematopoiesis.

Fig 1 – Diagram showing the location of the spleen, as well as its structure

Clinical Relevance – Splenomegaly

Splenomegaly is an enlarged spleen which can be caused by infection, portal hypertension, granulocytic leukaemia (increased lymphocyte and white blood cells), haemolytic and granulocytic anaemias etc. The spleen is usually not normally palpable in a GI examination but it would be in this case.

To assess the size of the spleen, a patient’s abdomen should be palpated diagonally from the right iliac fossa (RIF) to LUQ as it tends to enlarge towards the RIF. The underlying cause for the splenomegaly should be treated and in some cases, a splenectomy (removing the spleen) may be suggested.

Fig 2 – CT scan showing splenomegaly

Clinical Relevance – Asplenia

Asplenia is the lack of a functional spleen. It can be congenital or acquired (due to splenectomy). Patients are left immunocompromised and therefore are at a higher risk of acquiring infection from encapsulated bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria meningitidis.

To reduce this risk, these patients are given lifelong prophylactic antibiotics; immunisation for the above-mentioned organisms and annual flu vaccines. They should seek expert advice at first signs of infection.

These patients also carry an asplenia card/pendant/bracelet to alert healthcare professionals about their condition.