Puberty is the term used to describe the developmental changes a child undergoes to become sexually mature and physiologically ready for reproduction. It normally begins between the ages of 8-14 in females and between the ages of 10-16 in males.

In this article, we will discuss the hormonal and physical changes that occur during puberty in boys and girls and its clinical relevance.

Hormonal Changes

Puberty and the reproductive system are controlled by the hormones of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. The hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone (GnRH) in a pulsatile manner, which stimulates the release of Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) and Luteinizing Hormone (LH) from the anterior pituitary gland.

FSH and LH act on the gonads (ovaries/testicles) to stimulate the synthesis and release of the sex steroid hormones (oestrogen/progesterone and testosterone) and support gametogenesis. These sex steroids exert many effects on the reproductive system and feedback negatively on the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland to ensure that circulating levels remain stable.

During childhood the levels of FSH and LH in the body are low. This is thought to be due to the slow cycling of the GnRH pulse generator in the hypothalamus. Approximately a year before the first physical changes of puberty there is a rise in the pulsatile release of FSH and LH, as a result of the GnRH pulse generator being released from CNS inhibition.

The rise in FSH stimulates an increase in oestrogen synthesis and oogenesis in females and the onset of sperm production in males. The rise in LH stimulates an increase in the production of progesterone in females and an increase in testosterone production in males. As a result of these hormonal changes, the physical changes associated with puberty begin to develop.

The speed of development varies greatly between children, as genetic factors contribute. It is also suggested that body weight influences the onset of puberty.

Physical Changes

Puberty in Females

Thelarche

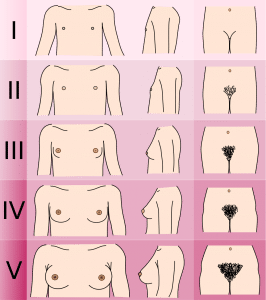

The first sign of puberty in girls is the beginning of breast development (thelarche). This typically occurs at around age 9-10. Breast buds appear as small mounds with the breast and papilla elevated. Tanner staging is used to assess breast size/development with stages I-V (shown below).

The breasts consist of lobulated glandular tissue embedded in adipose tissue, separated by fibrous connective tissue. Following the clearance of placental oestrogens after birth, the breasts are in a dormant stage until puberty. In this dormant stage, there are only lactiferous ducts with no alveoli.

At puberty, the increase in ovarian oestrogens causes the development of the lactiferous duct system as the ducts grow in branches with the ends forming the lobular alveoli (small, spheroidal masses). Mediated by progesterone, these lobules will increase in number through puberty.

The breasts continue to increase in size following menarche due to increased fat deposition. Throughout the menstrual cycle, oestrogen and progesterone affect the breast size and composition.

Fig 1 – Tanner staging in females

Pubarche

The second sign of puberty in girls is typically the growth of hair in the pubic area. The hair initially appears sparse, light and straight; however, throughout puberty, it becomes coarser, thicker and darker.

Approximately 2 years after pubarche, hair begins to grow in the axillary area as well. In both sexes, hair growth is a secondary sexual characteristic mediated by testosterone.

Menarche

Menarche is the first menstrual period and marks the beginning of the menstrual cycles. It normally occurs around 1.5-3 years after thelarche and is due to the increase in FSH and LH.

The menarche process typically occurs at ~12.8 years (+/- 1.2 years) for Caucasian girls and 4-8 months later for African-American girls.

Puberty in Males

Genital Changes

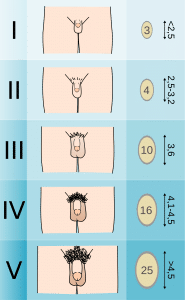

The first sign of puberty in boys is the increase in testicular size. The increased LH stimulates testosterone synthesis by Leydig cells and the increased FSH stimulates sperm production by Sertoli cells. Spermatogenic tissue (Leydig cells and Sertoli cells) makes up the majority of the increasing testicular tissue. The progression of testicle size can be measured by tanner staging from stage I to stage V.

As the testicles increase in size the scrotal skin also grows and becomes thinner, darker in colour and starts to hang down from the body. It also starts to become spotted with hair follicles (these appear as little lumps.)

Approximately a year after the testicles begin to grow, boys can experience their first ejaculation because the testicles are now producing sperm as well as testosterone. The first ejaculation marks the theoretical capability of procreation. However, on average fertility is reached one year after the first ejaculation.

The growth of the penis follows the testicular enlargement. The penis first grows in length. Then the width of the penis increases as the breadth of the shaft increases. The glans penis and corpus cavernosum also enlarge.

Pubarche

Another pubertal sign in boys is the growth of pubic hair at the base of the penis (pubarche). This often occurs alongside testicular growth. Pubic hairs will initially be light-coloured, straight and thin; however, as puberty progresses they become darker, curlier, thicker and more widely distributed.

Approximately 2 years following pubarche, hair also begins to grow on the legs, arms, axillae, chest and face.

Fig 2 – Tanner staging in males

Growth Spurt (Males and Females)

The pubertal growth spurt is the product of a complex interaction between the gonadal sex steroids (oestradiol/testosterone), GH and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). GH levels will rise in puberty due to the increase in sex steroids (testosterone which has been converted to oestradiol) and their positive effect on the pulsatile release of GH from the anterior pituitary gland.

A rise in GH causes a rise in the anabolic hormone IGF-1, which causes somatic growth via its metabolic actions (e.g. increases trabecular bone growth.)

Following the peak of the growth spurt in males, the larynx and vocal cords (voicebox) enlarge, and the boy’s voice may ‘crack’ occasionally as it deepens in pitch.

Clinical Relevance – Precocious Puberty

We define precocious puberty as the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics before the age of 8 in girls or before the age of 9 in boys. There are a variety of causes/types:

- Iatrogenic – this occurs as a result of exposure to exogenous oestrogens, e.g. via creams or lotions etc.

- True/complete – due to early maturation of the HPG axis resulting in high levels of GnRH, FSH and LH. This may be due to CNS lesions near or in the posterior hypothalamus, CNS neoplasms, hamartomas, and primary hypothyroidism.

- Incomplete – due to increased levels of oestrogens in girls and androgens in boys that are independent of GnRH.

Precocious puberty may either be isosexual (early sexual development consistent with the genetic and gonadal sex of the child) or contrasexual (early sexual development associated with feminisation of a male or virilisation of a female).

Clinical Relevance – Delayed/Absent Puberty

We define delayed or absent puberty as the absence of secondary sexual characteristics by the age of 13 in girls or 16 in boys. There are various causes:

- Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism – this is due to a disorder of either the hypothalamus or the pituitary gland. The disorder results in a deficiency in GnRH, LH or FSH.

- Hypergonadotropic hypogonadism – this is due to a disorder of the gonads (ovaries or testicles.) The disorder results in absent or reduced gonadal steroid secretion which results in high circulating levels of LH and FSH as there is minimal negative feedback from the gonadal steroids on the pituitary gland.

- Clinicians may see multiple conditions associated with delayed puberty. Be careful to watch out for these in exams:

- Turner syndrome (45 XO)

- Klinefelter syndrome (47 XXY)

- Androgen insensitivity syndrome

- Kallmann syndrome

- When investigating infertility, consider other conditions that are not congenital.

Doctors can treat severe delayed/absent puberty with carefully controlled hormonal replacement therapy.